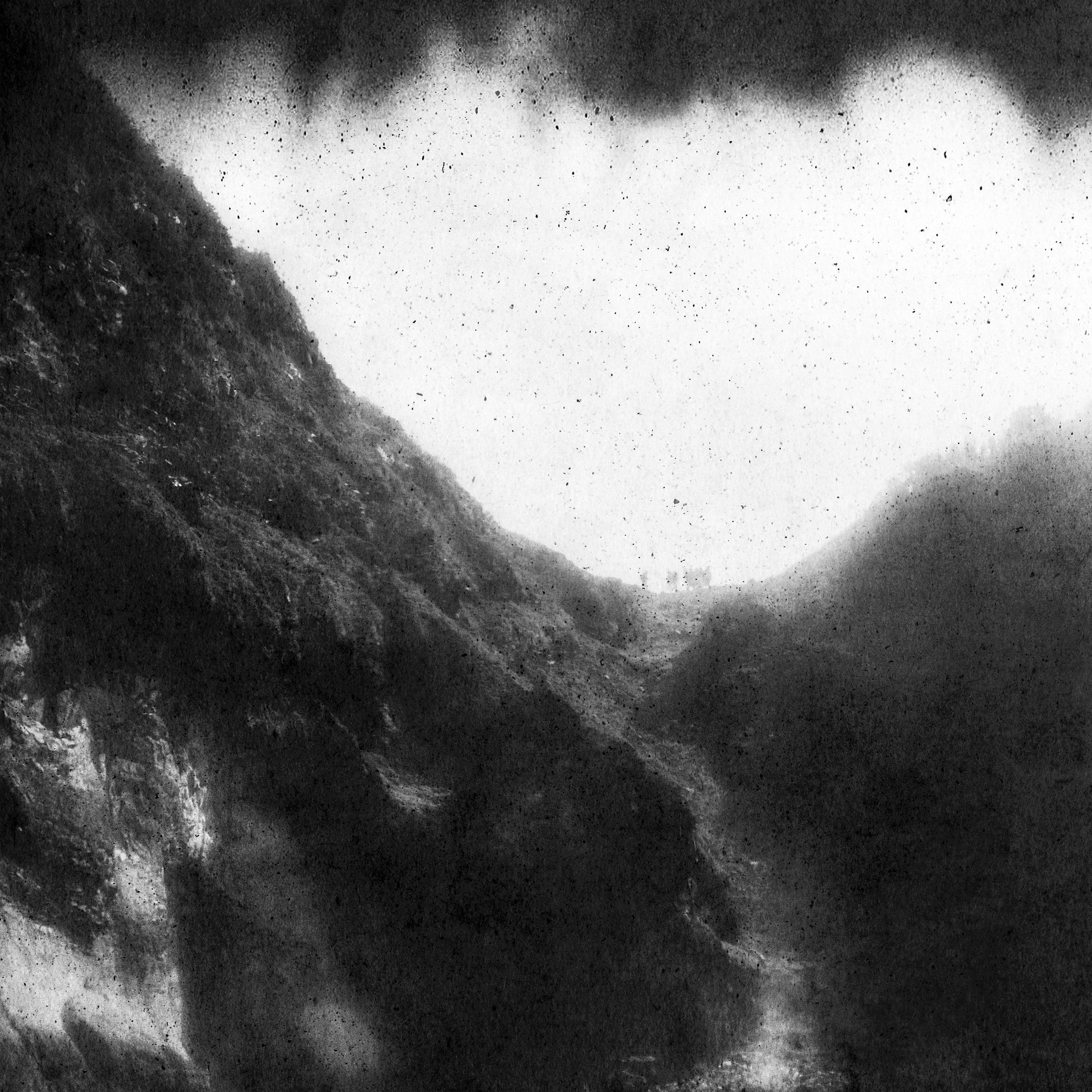

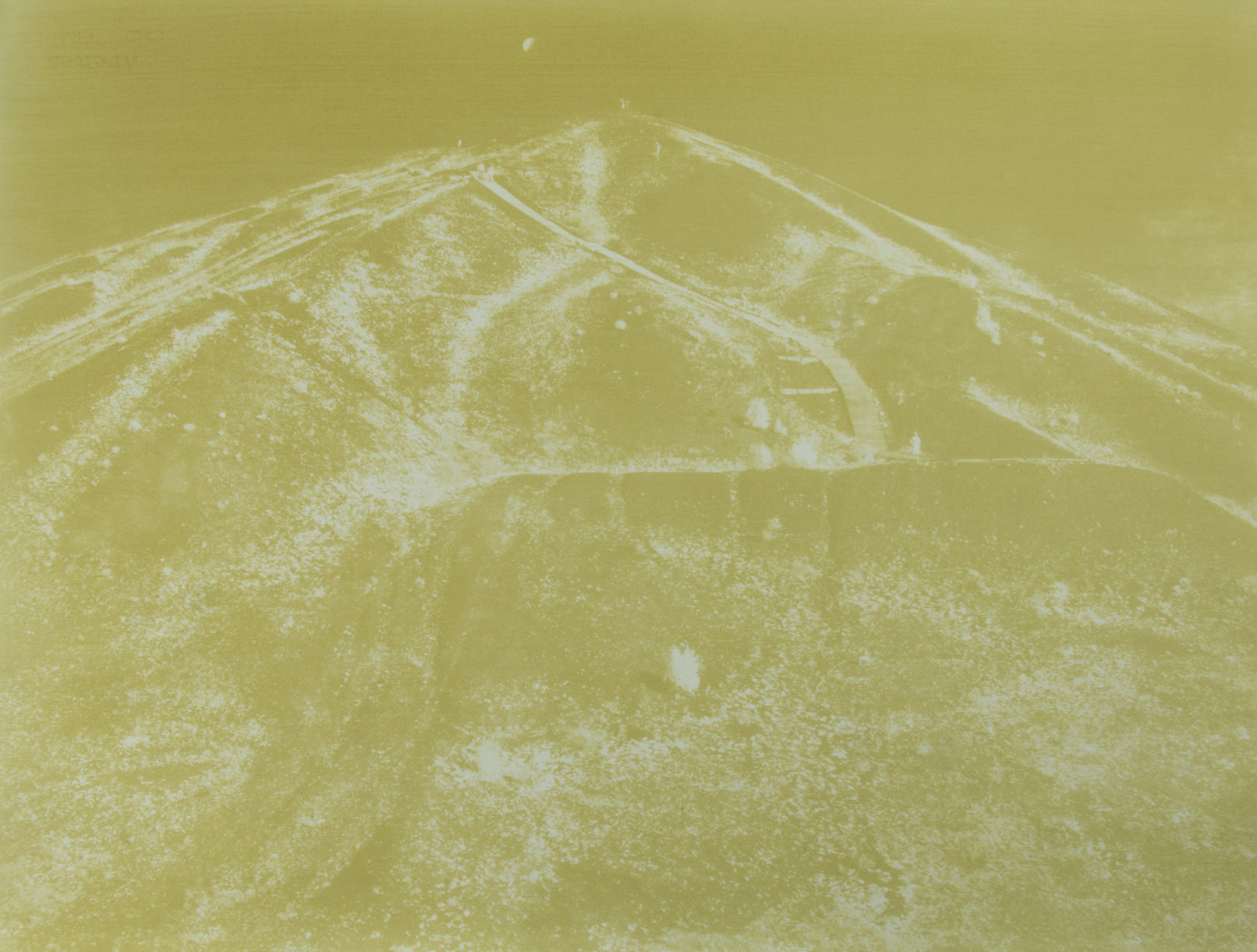

Présage, Hideyuki Ishibashi

Each of Hideyuki Ishibashi’s works is an iteration of the burning desire to get a grasp on time. What if images, or more precisely the initiatory process of making them, could mend the wounds of painful memories? Memory itself is a moving archive leaving a trail in our mind, a series of emotional and visual imprints evolving and lingering. What would an image that is the crystallization of a thousand moments look like? The images Hideyuki Ishibashi produces are geological strata, the accumulation of many layers of processes – analog and digital palimpsests.

Combining contemporary tools with ancient photographic chemical processes, such as gum bichromate or cyanotype, Hideyuki Ishibashi constantly pushes the limits of printing techniques. After a long period of producing cameraless images, collages and digital manipulations of personal or found archives, his recent cycle of works marks the return of the camera apparatus he had left aside for a while.

Leaving the studio to take pictures again has made wandering and displacement an integral part of his artistic researches. In contrast, previous works such as Présage and Other Voices had no defined location but limbos between memories and dreams. They took place in mental spaces, projections of personal wounds diluted into paper and light.

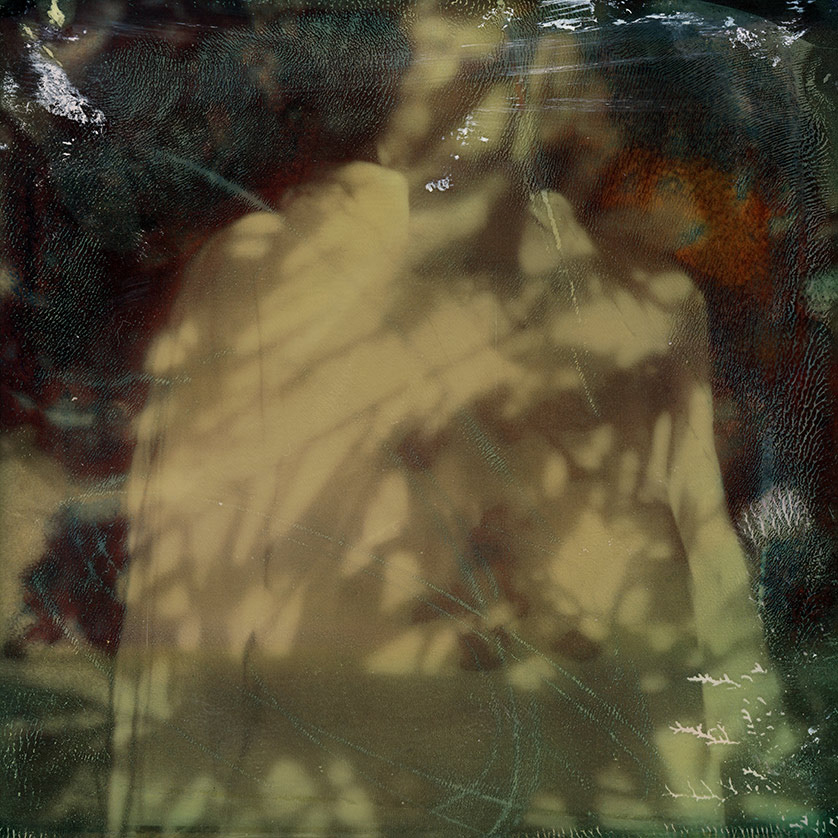

Other Voices departs from negatives portraying a loved one. The latent images, as a painful reminder of his absence, were left undeveloped for a long time. “The photograph of the missing being (…) will touch me like the delayed rays of a star.” said Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida. When looking at an image is too difficult, and destroying it is impossible, what is there left to do? In order to be able to lay eyes on these images again, Hideyuki Ishibashi photographed them multiple times with a Polaroid, adding new layers of time and visual information at every step of the process – reflections, shadows, fingerprints on the surface. Past and present merge in the resulting images, echoing how time transforms memories.

Other Voices, Hideyuki Ishibashi

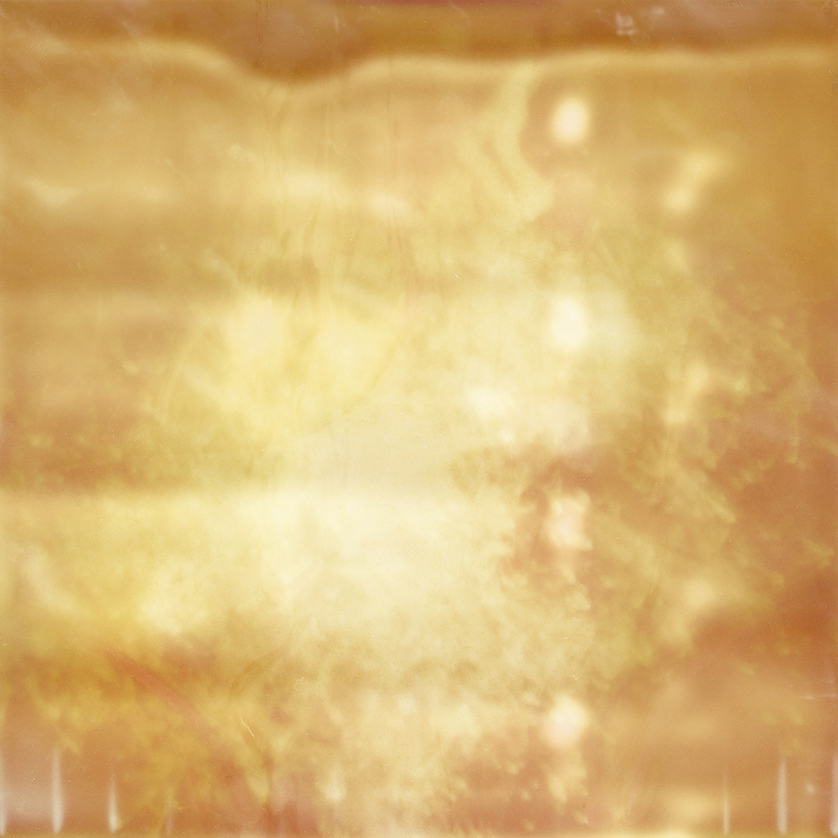

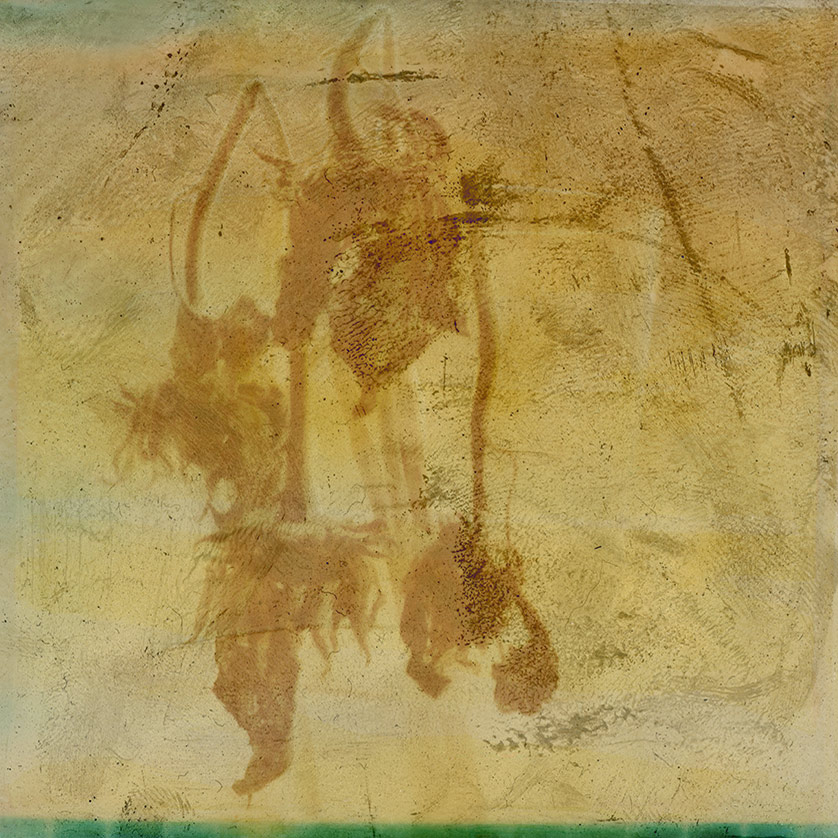

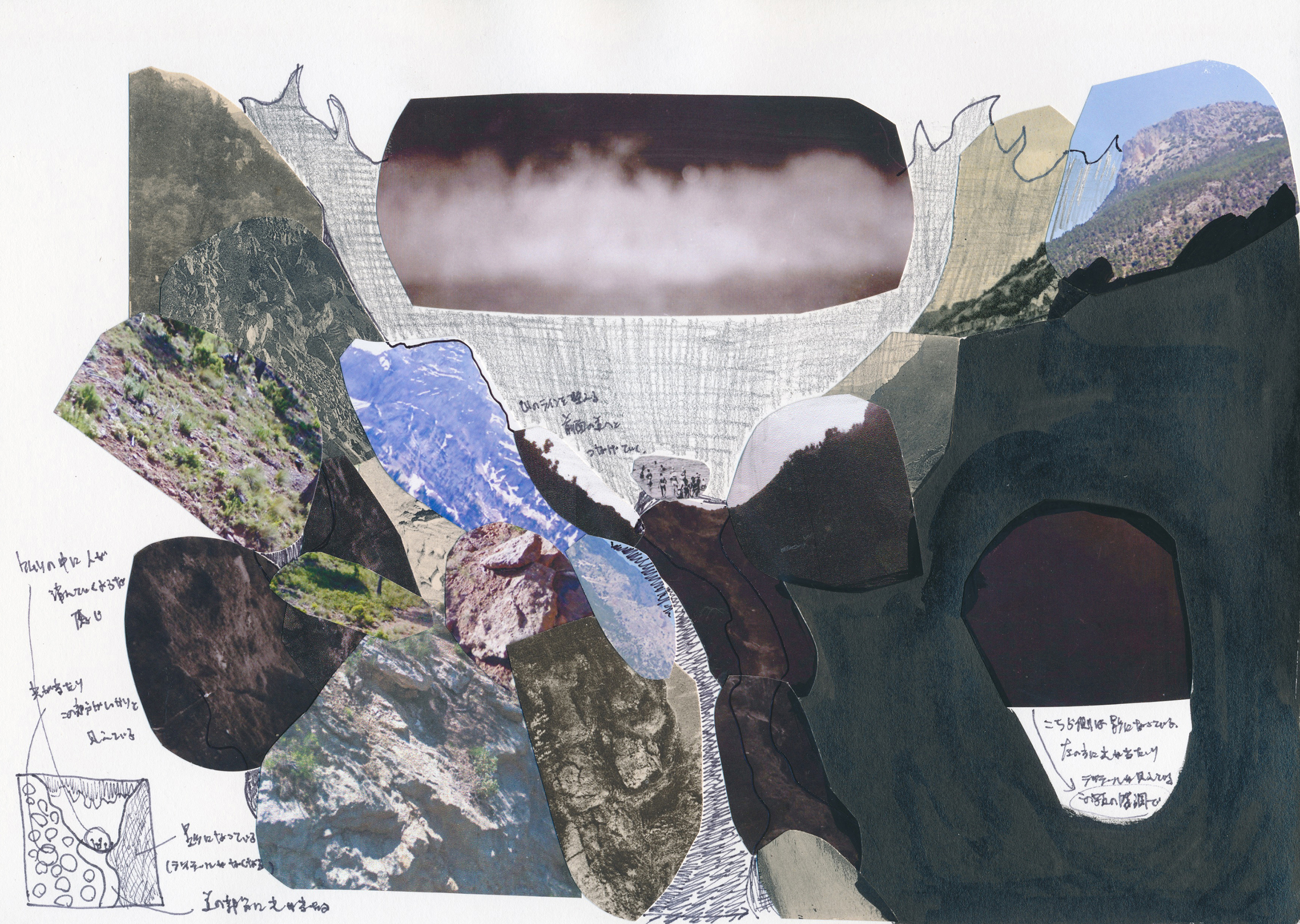

In Présage, dream-like scenes are materialized through a complex series of manipulations, recomposition, and assemblage. First there are visions. Every morning for a while, Hideyuki Ishibashi drew the fleeting images still lingering in his mind when he woke up: a fire, a forest, silent dramas, the shadow of a lonely man, silhouettes on a hill. But were they really dreams? Présage is haunted by memories from the terrible Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in Kobe, witnessed by the artist when he was 9 years old. The forces of nature turned the familiar urban landscape upside down, theater of unsettling scenes. The traumatic impact of this event merges with the subconscious to produce mental scenes, reconstructed little by little from small printed fragments cut from Google Street View screenshots and found photographs.

At this point the composite collage is a chimera, an assemblage of roughly cut shapes adorned with notes and sketches: here an arm, there the branch of a tree, colorful masses of textures outlining the composition. In the next step, the collage is scanned and reassembled with Photoshop. The colorful details, meticulously unified in black and white, merge into each other. After ‘’completing corrections to an almost impossible degree‘’, the artist blurs the distinction with a real photograph. These two projects could be considered utopia as well as uchronia. Out of space, out of time.

Présage, Hideyuki Ishibashi

On the contrary, his most recent works are topical, deeply anchored in specific locations and their seasonal or circadian cycles. The subjects are environments shaped by human presence: gardens, artificial forests, mountains of slagheaps located in the North of France, where the artist currently lives. This constructed nature is treated as human projections, where the artist looks into himself, and at his own relationship to nature; self-portraits in the shape of slagheaps or a gingko leave.

These connections with a specific environment go along with a shift in printing techniques, bringing Hideyuki Ishibashi to take into account the ecological impact of chemical products and consider the toxicity of the photographic industry. He started to produce his own paper and vegetal pigments from plants patiently gathered in the depicted landscapes, making prints as physical incarnations.

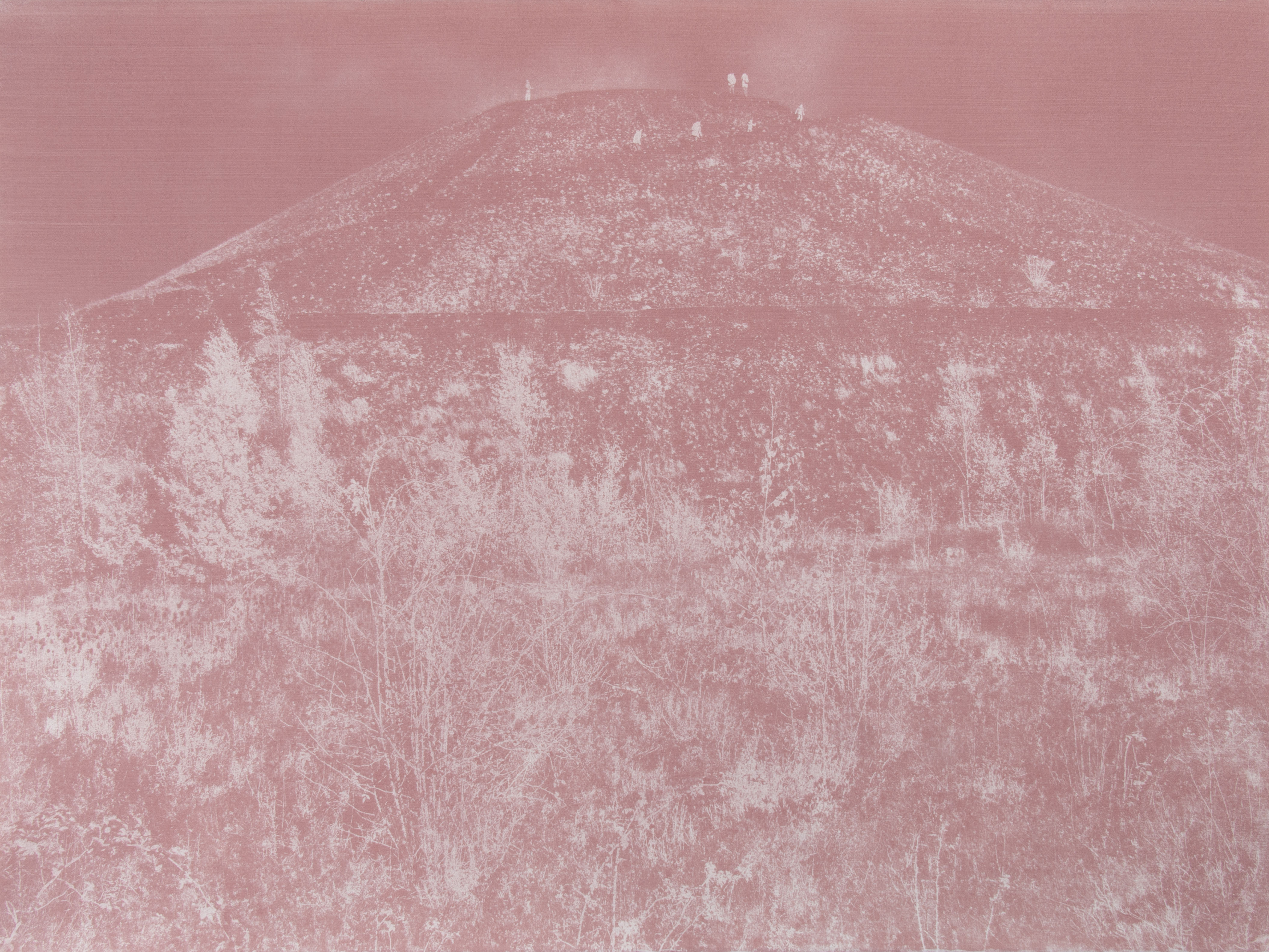

For his series Chromophore, Hideyuki Ishibashi portrays 12 slagheaps from the Hauts-de-France region, illuminated from within by a radiant light. An infrared camera highlights the various plants; beyond the view of the slagheap itself, it is its vegetation he’s interested in. Hideyuki Ishibashi’s process is closely related to seasonality.

After choosing twelve plants representative of each slagheap’s ecosystem, he collected large quantities of them. Back in the studio, the plants are dried and crushed into pigments, smell and color merging into a sensorial experience. A subtle scent later remains as a discrete emanation from the paper, bringing the bark of St Lucie cherry tree or perennial wall-rocket into the exhibition space. Natural pigments have a different saturation than chemical ones. To obtain vivid colors despite their transparency, Hideyuki Ishibashi multiplies layers of print – each of them taking approximately one hour.

When he hangs the paper to dry, insects come. Observed with an UV light, the prints reveal fluorescent hues. An insect vision probably mistakes them for flowers. These fleeting prints are alive, like us, like the landscape they’re an imprint of. Over time, the chlorophyll will disappear. They might need to be kept in the dark, only revealed from time to time, making its contemplation a precious and rare experience.

Chromophore, Hideyuki Ishibashi

When visiting locations for this project, Hideyuki Ishibashi remembered the first time he set foot on a slagheap. It was on a snowing day. He was then struck by the contrast of white snowflakes on the dark soil, making the slagheap appear like a black and white imprint of human activities, a mountain of memories with a burning core.

Walking on the location of a recent fire, Hideyuki Ishibashi was surprised by the smell of ashes and the warmth of the ground still burning beneath, recalling sensorial flashbacks of the Kobe earthquake in 1995. The slagheaps are sometimes subject to natural or arson fires, turning the colorful vegetation into a black monochrome landscape of ashes and burned trees before a new life rise again. He took pictures of the burned plants and buried the resulting film underground, leaving the heat to alter the chemical matter and destroy part of the image. Gathered ashes were transformed into black pigments for photopolymer etching prints of these burnt images.

Hideyuki Ishibashi made his own paper to print Fossil, in which shadows of branches and leaves play with the contrast between the positive and negative space of the composition as well as the use of these terms in photography. His paper recipe draws from Japanese artisanal papermaking where plants, mostly mulberry, are used to produce the washi paper. The environment in which the plants grow, and the purity of water have a great influence on the quality of its final quality. The smoothness of traditional washi makes way here for a very textured paper. Hideyuki Ishibashi deliberately leaves stems and seeds visible at the surface. The photographic print becomes a tactile object, a surface with landforms, like a fossil of the landscape it represents. It acts as a living archive of its vegetation, and a potential for the future; if the prints were planted, the seeds contained in the paper would grow.

Burning Ground, Hideyuki Ishibashi

As a reaction to the visual accumulation that defines our contemporary era, Hideyuki Ishibashi summons numerous techniques whose time-consuming process contrast with the limited attention span dedicated to images online. What Hideyuki Ishibashi mends is also a relationship to our senses when making and consuming images, sliding away from digital ‘’slippery images like the iridescent slime of a snail‘’ * that we scroll every day, texture-less and flat.

*Respirer l’ombre, Giuseppe Penone

MORE articles

Bouche – Lucile Boiron

Plus lentement que le passage d’un nuage, mais plus vite que la naissance d’une ride – Delphine Wibaux

Nous sentons les couleurs avant de pouvoir les nommer – Christine Berchadsky

First Mother is a temporary space – Bárbara Prada